17 Aug Ronald McDonald House School kicks off new year

School aims to maintain ‘sense of normalcy’ for sick children and siblings

Fri, Aug 17, 2018, 6:50 am

Each day before class at the Ronald McDonald House School in Palo Alto, students recite the school’s creed. They promise to be kind, rise to life’s challenges and be the best that they can be. For students who attend the school, which primarily serves ill children and their siblings who are staying at the facility during medical crises, teacher Catherine Enos hopes that the daily routine of repeating the creed will provide them with necessary consistency.

“Everyone comes here with the intention to make this a safe and caring space for students,” Enos said. “We want to support them in what can often be a traumatic time in their life.”

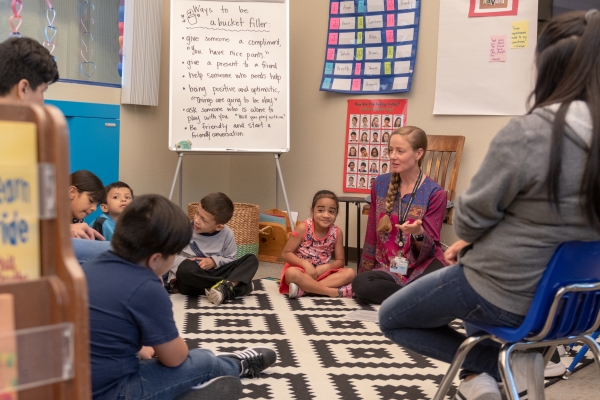

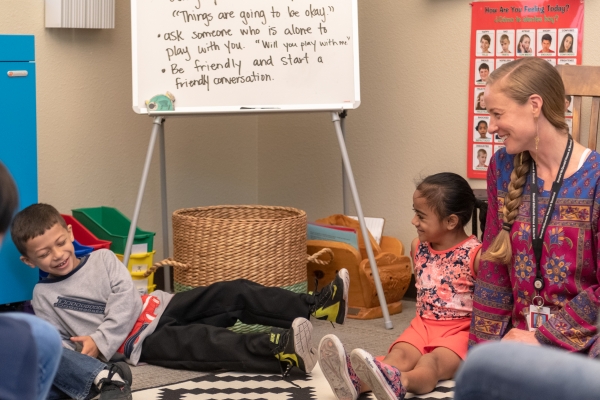

Teacher Catherine Enos, right, leads a name game at the Ronald McDonald House school with students Francisco, at left, Angelnetta, in the middle, on Aug. 14, 2018. Photo by Adam Pardee.

The Ronald McDonald House School started a new academic year this week with eight students, new programming and a growing partnership with the Palo Alto Unified School District.

The school consists of one classroom for kindergarten through high school students; one full-time teacher (Enos); an arts studio and a new makerspace full of materials for 3D printing and circuit building. Bri Seoane, director of programs and operations for Ronald McDonald House Charities Bay Area, described the school as “the Little House on the Prairie one-room schoolhouse.”

Inside the clean and cheerfully decorated classroom on the first day of school, students warmed up by playing a name game, with each saying his or her name and answering two questions: what they like to do on a hot day and who their role model is. Some students answered shyly; others eagerly talked about their role models.

On a white board, “Ways to be a bucket filler” — that is, how to encourage another person — were spelled out, including “Ask someone who is alone to play with you” and “Give a compliment: ‘You have nice pants.'”

Last year, the Ronald McDonald House School became a full-time Palo Alto Unified School District site. Before that partnership, the school struggled with a lack of structure and resources, Seoane said. Its teacher was part-time and only taught two hours a day. In the 2016-17 school year, before its partnership with the district, the school served 22 students. Last year, the school served 140 students, many of whom traveled across the country to receive care at Stanford Hospitals and Clinics.

Ronald McDonald House students receive the same resources from the district as other students, including curriculum, laptops, iPads, textbooks and online materials.

Many students don’t know how long they will attend the Ronald McDonald House school, since students’ and families’ time is dictated by medical care. On average, 30 percent of families stay for longer than two months, according to the organization. Typically, there are eight to 16 students attending the school at one time, Seoane said.

“Some students will be here for a couple days and may just need help staying afloat with their schoolwork they’re given from their teacher,” Enos said. “For students who are here longer term, we need to design curriculum for them. … We work with the students to make sure they have continuity.”

Enos coordinates with a student’s home school to develop specially designed lessons for each student. Often, students are behind because they come from a less-resourced district or have been frequently pulled out of school to be with their sick sibling or to attend to their own medical needs. With specialized attention, Enos said students are able to explore their interests more, while catching up on school work.

Socially and emotionally, students often thrive by learning alongside others who share the experience of having a critically ill sibling or being critically ill themselves.

“There’s that organic support that happens. The students speak their own language to a degree,” Seoane said. “Oftentimes when you hear them talking, you really don’t understand what they’re saying because it’s medical shorthand.”

The school first started discussing a partnership with the Palo Alto district in 2012, when administrators realized that the school district had a legal obligation to serve outpatients and the siblings of patients. They also learned that Ronald McDonald House families fall under the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, a federal law that provides resources for people in transitional housing situations. Under the law, transportation and other support resources are available for the school’s students and families without permanent addresses.

Now, school staff and family-support coordinators from the district help families enroll at the school and transfer into traditional schools. The partnership allows students to earn course credit, receive official grades and access district specialists and parent aides.

“We’ve tried to remove barriers from the students attending school,” Seoane said. “It’s a really difficult thing for a parent to navigate a school district that you’re not from, while it’s the middle of the school year and you’ve got a lot going on with your sick kid.”

In addition, bilingual district staff and Enos work with the many Ronald McDonald House families who only speak Spanish to help them find the resources they need.

This year, the school is continuing to evolve to meet students’ needs. The school has added 30 minutes for breakfast to the schedule, as last year many students were coming to school without eating anything beforehand. The school also added a supervised lunch hour along with outdoor activities and play time. Last year, parents had to pick up their children during lunch, feed them and drop them back off at school, but oftentimes students wouldn’t come back in the afternoon.

The school is also looking to grow its enrichment opportunities with frequent art classes and weekly drama sessions run by professional theater company TheatreWorks. The program is still in need of more teaching aides and volunteers, especially those who can consistently come every week, Seoane said.